By Jordan Butler

You’re at a party, about to try a dessert a friend promises will “change your world!” Intrigued and excited, you take your first bite. Only then do you find out this mysterious dessert is actually just a dry, dressed-up fruitcake, decorated to conceal its re-gifting. You feel disappointed and annoyed your friend.

Like that disappointing dessert, I’ve heard stories with a similar arc as Design Thinking has grown in popularity. Often diluted and over-simplified, some Design Thinking approaches over-promise and under-deliver, breeding an appropriate side effect: skepticism. Design Thinking is not a magic bullet that will perfectly solve all your problems. It’s much messier, richer, and more interesting than that — and much better than fruitcake.

A Graphic Story.

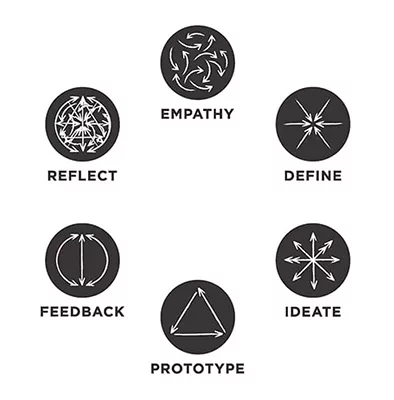

Wondering what we mean by Design Thinking at HFLI? We describe it as a collection of mindsets and methods that allow us to creatively explore problems, then reframe and act on them. A key point: it involves action, or “design doing”, as well as thinking. These methods and mindsets go back decades and draw from the work of systems thinkers, psychologists, anthropologists, design researchers, architects, and scientists to name a few. The learning experiences we create and deliver for educators, social entrepreneurs, workplace learners and youth embody this philosophy. Initially, HFLI’s Design Thinking graphic looked like this:

The diagram implies a step-by-step process and highlights the distinct phases within that process, which was a great place for us to start when we began our work with the d.school and IDEO back in 2006. However, over time our team has come to the more nuanced understanding that Design Thinking actually looks more like this:

And sometimes even like this:

Design Thinking (and remember that also includes doing) is messy. Complex challenges require a consistent looping back and around to check assumptions, reframe problems, and iterate on prototypes. Everyone has experiences, skills, and expertise from outside of Design Thinking to inform the process and make it richer, as represented by the blank circles in the diagram above. As HFLI considered the initial graphic and how it could evolve, three ideas guided us: Design Thinking is not a closed loop, Design Thinking is not linear, and Design Thinking is not static.

Design Thinking is not a closed loop.

Looking at our initial graphic, the arrows create a closed circle and imply a self-contained process. Sure, these six steps can be an effective way forward when navigating ambiguity, but in the same way that quantitative research doesn’t always capture the whole story or that Lean Startup isn’t always the right methodology, Design Thinking can’t answer everything. To truly be at it’s best, Design Thinking must be open to critique, expand to include new ways of working, and draw from diverse disciplines.

A favorite quote of mine comes from Charles Eames. In an interview he responds to the question, “What are the boundaries of design?” with another question, “What are the boundaries of problems?” As we continue to learn how design strategies can be applied to the intractable problems in education and society, it’s exciting to imagine how Design Thinking will deepen, grow, and push to the edge of those far-reaching boundaries. To do this, it cannot be a finished, closed process, which also means it most likely doesn’t take the shape of a single, smooth line.

Design Thinking is not linear.

Replicable A+B+C+D=E formulas appeal to the desire for efficiency and expedient solutions. However, social problems are complex, and arriving at clarity in the midst of that complexity is often extremely difficult. To push the boundaries of design and problems, the frameworks used must be sophisticated and nuanced enough to respond. Here, Design Thinking and doing draw on the strengths of iteration and exploration through making.

For example, let’s say I am using Design Thinking mindsets and methods to work with a nonprofit that wants to reimagine how it engages with the issue of homelessness and shelter. As I walk through the Design Thinking process with them, we don’t check off the Empathy box once we start to define a project problem statement. We go back to the Empathy phase over and over and over again based on new insights. That might mean seeking feedback on ideas from the nonprofit’s clients or staff members, confirming the identified need with users, or learning more about the context of homelessness to check our assumptions along the way. In the same way, we don’t check off Define when we begin to imagine potential responses. As we generate ideas and explore them through making, our problem frame may shift and and be reframed multiple times. This idea applies to each of the phases.

Hopefully, it’s becoming clear why the process looks a little more like this in practice:

That leads to the next guiding principle…

Design Thinking is not static.

Design Thinking has changed and evolved over its lifespan, and it remains dynamic as the concept of “problems” transforms and as practitioners continue to add new research, tools, and methods to the framework. Maybe this collection of mindsets and methods from design won’t be called Design Thinking in the future. Maybe the language will change, and that is okay. These human-centered strategies will continue to help people ask critical questions, explore problems creatively, and reframe and act on those problems regardless of what jargon gets applied.

In an effort to reflect these principles, our team has taken what may seem visually like a baby step, but actually reflects a more nuanced understanding in our thinking and practice. For now, the arrows are gone, and our graphic looks like this:

Our team aims to practice and teach Design Thinking in a way that is open to and inclusive of other disciplines and methods, in a way that acknowledges the complexity involved in the process and doesn’t oversimplify, and in a way that continually evolves and expands. That’s what has led us to the rich place we’re at today in design, and that’s what will take us forward.

This story originally appeared on Medium. Interested in learning more? Contact us at designthinking@hfli.org